Is time, cost & quality really a triangle?

Andy Painting

Surely, it’s all about balance?

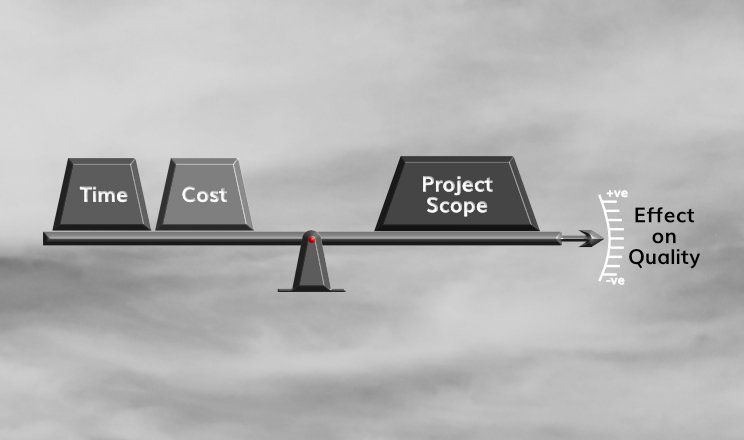

It’s fairly certain that just about everyone has either heard of, or has used in conversation, the term “time-cost-quality triangle”. It’s an expression that has been around for a long time and, for most people, reasonably portrays the effect that these three features have on any sort of undertaking. The inference is that if a change is made to any one of them, it will affect the other two. But is a triangle the best way to think of this relationship? Does it provide a visual demonstration of what really happens?

Imagine a project or undertaking as a balanced system: if all things stay the same throughout, then the end product or result will emerge with the required quality, and on time and on budget. It is, of course, sadly rare that any project goes 100% according to plan, however detailed that plan might be. All sorts of circumstances can emerge or evolve during any project, and any one of these can affect the intended output, causing time, cost or quality issues that have to be agreed. We did say “imagine” after all.

Many of these issues will have been recorded as risks to the project at the beginning. Risks like what will you find underground whilst piling; will the cost of steel increase; was the statement of requirements clear enough; are the right people involved in the design process; has someone just changed their mind on the specification? Some of these risks are associated with scope creep, a situation that means what has been priced and estimated against is no longer viable. Even changes that should make a project run more quickly, or smoothly, often have a negative effect by increasing redesign time or procurement of alternative materials. It’s very rare that a risk will have a beneficial effect on the project.

Understanding the scope of the project – the ultimate ambition of the statement of requirement, if you like – is important in ensuring we can identify potential scope creep as soon as possible. If we accept the changing scope of the project, and funding and timescales remain the same, the result will be a negative effect on quality. If, on the other hand, we don’t want to accept that our new car model will only have three wheels, then we have to compensate elsewhere in the project.

Similarly, allowing more time for the design or production phases, with a static scope for the project, will have a positive effect on the resultant quality of the output. This is the balancing of time, cost and quality that a simple triangle really cannot convey properly.

Understanding the potential risks at the outset of any design allows the client to make funding decisions based on their interpretation of the level of risk and the potential impact. Each client will have their own appetite for risk, as well as the organizational capacity to deal with some risks better than others. As the scope of a project increases it can be counterbalanced by the release of resources from the client, whether this is in the form of time, money or effort. Alternatively, the client may accept the impact that scope creep will introduce and deal with it downstream within the organization.

This is why it is extremely important to put far more effort into the start of any design or build project. The immediate upfront cost will, undoubtedly, be higher but the savings to be gained later on in the project – possibly even during the in-use phase of the end product – will invariably outweigh those costs many times over. It takes careful skill and expertise to recognize, at the very beginning of any project, what the foreseeable risks might well be and ensure that the client is properly informed as to the potentiality of impact to them. You could say, it’s a careful balancing act.

Latest News

Show More